If you are a long-term prisoner and you want to be released more quickly, you will need to satisfy the Parole Board that your risk has been reduced. If you are a “lifer”, then if you want to be released at all you will need to show that your risk has reduced. The usual means of showing the Parole Board that your risk has been reduced is by the completion of ‘accredited’ offending behaviour programmes (OBPs), run by the Prison Service on behalf of the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). One of the most familiar OBPs is the sex offender treatment programme (SOTP)

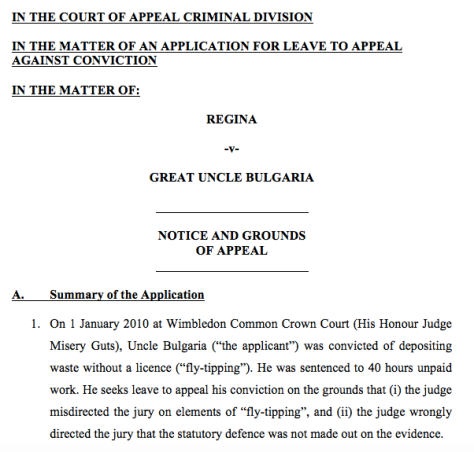

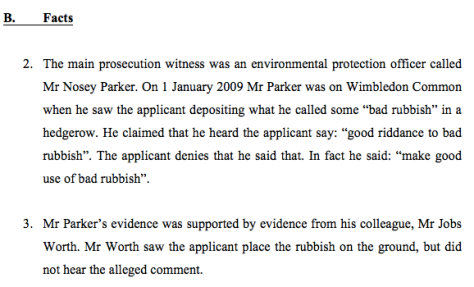

I first encountered the SOTP whilst a pupil barrister. I was instructed to attend at a high security prison for a parole hearing. My lay client, serving a life term, was told that he needed to do the SOTP, but that he could not do it because he denied the offence. It occurred to me that this seemed unfair. I argued from that position. The hearing was fractious. The panel did not welcome my submissions and my client was palpably angry and frustrated at his predicament. Some time after the hearing the client was told that he would not be released, which came as no surprise to any of us. He was not released until 8 years later: when his conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal. He had been innocent all along.

This is a stark but real-life example of the injustices that the SOTP could inflict. The programme was regularly criticised on the narrow (but compelling) basis that it is unfair to keep those who are innocent in prison unless they would feign guilt and do the SOTP.

We have now learned that this was not the only shortcoming with the SOTP model. Things, it transpires, were very much worse than that. Earlier this year rumours started flying about that the MoJ was sitting on some unpublished research which painted a damning picture of the SOTP’s effectiveness. It was then learned that the programme was to be quietly dropped.

On 24 June 2017 the Mail on Sunday published a piece by David Rose, in which he alleged that the MoJ was hiding evidence that the SOTP increased reoffending rates. If true this would undermine repeated reassurances from the MoJ – trotted out at many a parole hearing – that the programme was effective. A 2003 report by Dr Caroline Friendship, Dr Ruth Mann and Dr Anthony Beech, commissioned by the Home Office, looked at the effectiveness of the programme before 1996 (before it was “accredited”). Their research suggested that the programme had a significant positive impact on reoffending rates.

On 30 June 2017, and presumably in response to the David Rose article, the MoJ published the evidence. It is an “impact evaluation” of the prison-based core SOTP. The background to the use of SOTP in prisons, and its accreditation, is explained in the report as follows:

“Core SOTP is a cognitive-behavioural psychological intervention designed by the HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) for imprisoned men who have committed sexual offences. The Programme is intended to reduce sexual reoffending amongst participants by identifying and addressing known criminogenic needs. It was accredited for use in prisons in 1992 by the then HM Prison and Probation Service Prison and Probation Services Joint Accreditation Panel, which later became the Correctional Services Accreditation and Advice Panel (CSAAP).

The CSAAP help the MOJ and HMPPS to develop and implement high quality offending behaviour programmes and promote excellence in programmes designed to reduce reoffending. Programmes are assessed against a set of criteria derived from the “what works” evidence base. These include having a clear model of change, effective risk management, targeting offending behaviour, employing effective methods, ensuring relevance to individual learning styles, and maintaining the quality and integrity of delivery. Changes have been made to the targets, the content, and the methods used in Core SOTP since its introduction in response to emerging research. As a result, during the course of this study (and in the period thereafter) the Programme has changed. However, it remains a cognitive behavioural group based treatment approach. It was, and remains, available in approximately one-sixth of male prison establishments in England and Wales and is intended for individuals sentenced to 12 months or more, who had either a current or previous (sentence) sex offence, were willing to engage in treatment, and were not in denial of their offending”.

The evaluation used a large sample of offenders, with “treated” offenders matched to “untreated” offenders using a range of data sources. The results are devastating for proponents of the SOTP. In summary:

-More offenders “treated” with the SOTP committed at least one further offence within an 8-year follow-up period than those who had not been treated (10% versus 8%)

– More offenders “treated” with the SOTP committed at least one further child images offence within an 8-year follow-up period than those who had not been treated (4.4% versus 2.9%)

Also important is the report’s conclusion that the emphasis on groupwork generally may be problematic. Group treatment might “normalise” deviant behaviour, or even lead to the sharing of contacts or sources. This has been a gripe of lawyers (myself included) for many years. Some prisoners are reluctant to engage in groupwork. They do not want to talk about their offences in a group setting, or they do not want to listen to others talk about theirs. Some are frankly not keen on either. Such offenders have, for years, been told that if they won’t participate in group work then they can forget it. It was put up or shut up.

What recourse do such people have now? The answer is almost certainly none at all. In a litigation context the MoJ would say that it could not – before this research – have known that the programme wasn’t working They have started a new programme, Kaizen, to plug the gap that has been left.

But the MoJ were warned, repeatedly, that the SOTP was (or at least might be) defective. As reported in the Times on 1 July, Dr Robert Forde repeatedly challenged the mantra that the SOTP was working. In response he was on the receiving end of misconduct complaint: accusing him of being “insufficiently familiar” with the literature in this area. Thankfully, but perhaps unsurprisingly the complaints were not upheld. Similar warnings were raised by another psychologist, Dr Ruth Tully, who was excommunicated by the MoJ as a result.

The MoJ cannot in good faith say that it did not – or could not – see this coming. It was there to be seen if only they had been willing to look. Lawyers have been banging their heads against prison walls for years trying to challenge the assumption that the programme did what it said on the tin. They are not the victims in this of course; nor are the psychologists who spoke up. It is the public that has suffered from this failed experiment, and those offenders who remain stuck in a system that demands of them a reduction in risk whilst failing to offer any realistic or effective means of them doing so.

The new Kaizen programme accepts prisoners who are maintaining their innocence. This is a significant and positive change. I hope that the programme succeeds; that it keeps the public safe and allows offenders to be released more speedily. But Dr Forde argues that the new programme is based on the same discredited techniques as the old one. Based on historical events, his is a voice that must be listened to.

And it is not just the MoJ that could usefully open its ears. For too long the Parole Board failed to question the “official” position on the SOTP. The Board has changed a lot since that hearing back in 2005, and mostly for the better. It is an independent body but it must be fiercely so. Because even the proponents of accredited behaviour programmes can no longer maintain that it is not right to challenge and scrutinise “accepted” thinking about the treatment of offenders.

@thepubliclawyer, 2 July 2017

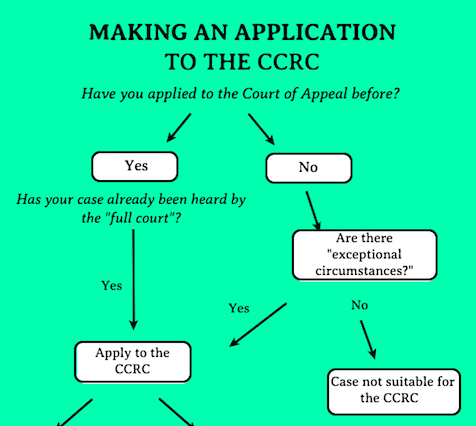

What if the CCRC rejects my application?

What if the CCRC rejects my application?